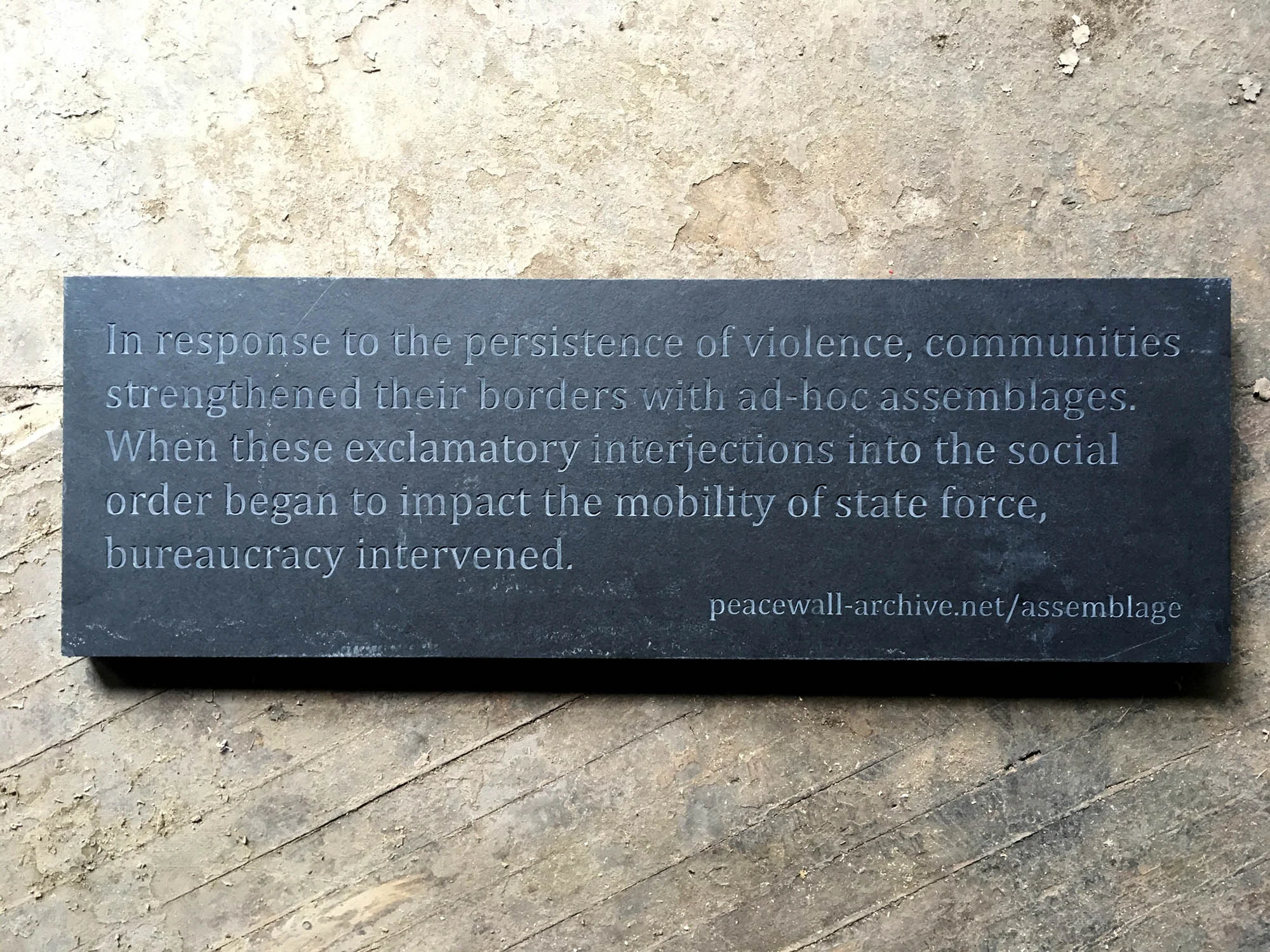

Assemblage

This text was instigated at Paragon Studios in Belfast for the exhibition PALISADE.

(Part of the #Peacewalls50 Series of events)

It will develop over the course the exhibition.

/ Future Policy on Areas of Confrontation /

I am sitting in the Director’s office of the Belfast Interface Project. It is 10 December 2014, and Strategic Director Joe O’Donnell hands me a photocopy of a recently uncovered thirty-eight-page report written by John D Taylor – then Minister of State in the Government of Northern Ireland on “Future Policy on Areas of Confrontation” dated April 1971.(*) The document has the familiar off-centre quality of canted text and markings of a document that has been photocopied numerous times, revealing a residue of dots, disappeared staples and paper folds. In the report, Taylor and his team propose that future planning in Belfast should provide “the maximum natural separation between the opposing areas through some sort of cordon sanitaire”.(*) It specifically states that the number of access roads between the Falls and Shankill should be “substantially reduced”, and proposes the construction of infrastructure, factories and warehouses between conflicting areas, with high walls to “form natural barriers”. The following day I look at the outcomes of this policy defined in 1971. Decades on from the publication of the Taylor Report, the ‘temporary’ Falls/Shankill peace-line mentioned in the document has grown into an extensive urban barrier of concrete, steel, sheet metal and mesh. I photograph the extent of this barrier from one end at the Westlink motorway that encircles Belfast city centre to its termination on the lower slope of Divis mountain on the western side of the city. These photographs form the starting point of the Peacewall Archive, an ongoing project which aims to provide a definitive online documentation of the Belfast 'Peacewalls’. [www.peacewall-archive.net]

/ Sedimentary Memory /

“You will never have a Berlin moment in Belfast” (where the walls come down overnight). I have heard this statement multiple times in my walks across Belfast. Too many times. I think of these words while sitting in a chapel of reconciliation in the Mauer Park along Bernauer Strasse. This contemporary church replaced a neo-gothic church of reconciliation that by fate of its location, ended up stranded inaccessible in the middle of the ‘death strip’ of the Berlin Wall. Imprisoned within its surrounding voidspace from 1961, and stripped of its congregation, the church was blown up on the order of the GDR Government in 1985, after seven years of negotiations. Remnants of the ruins of that church were mixed into the rammed earth walls that now form the enclosure of this new space, the thick walls providing welcome cool on what is the hottest day of the year. Traces of the previous building can be seen in the form of splinters of wood, shards of stained glass, pieces of burnt shaped stone and fragments of ceramic tile. They constitute a ‘sedimentary memory’ and a material record - an archive of sorts, embedded within the new earthen walls of the church. Some day, I wonder, will young organ students practice clumsily in a chapel of reconciliation along a line where the peaceline used to be?

-26th of July, 2019, Rewriting the Map, Berlin